This let you fiddle knobs to create a more optimal resolution and compression ratio for your purposes. The older versions of QuickTime, notably QuickTime 7 Pro, and older versions of iMovie let you dig into settings much further. (This is called transcoding if you’re converting from one format to another.) That decoding restores the original frames as if they were uncompressed, and then then applies your new export options.

But when you export a clip, the software has to decode it and then re-encode. When QuickTime Player and other software plays back a video, it decodes the compression, and modern iOS and Mac (and other makers’) devices have built-in chips that handle that decompression for real-time playback, rather than handling it in software.

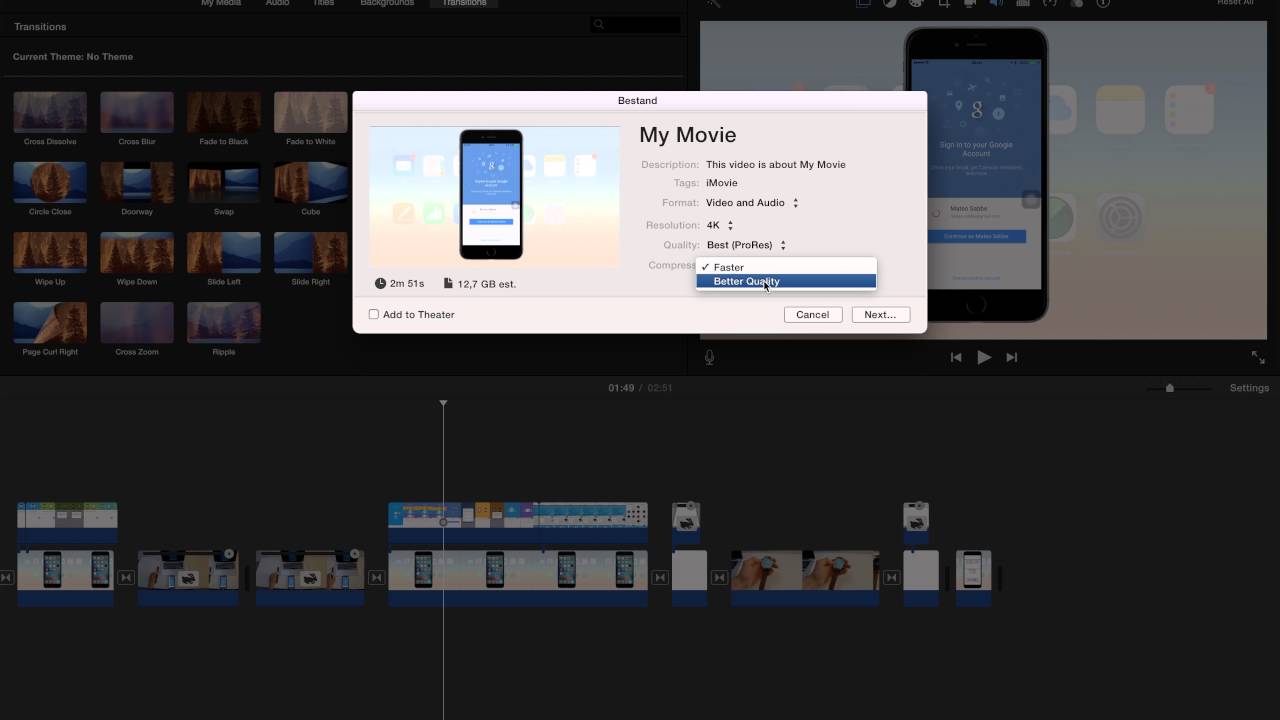

The higher fidelity you want, the more tonal and motion variations are preserved, and the bigger the file. So, when messages like this surface, go back and verify if your file name has special characters included on it. If a large area of an image or frame is more or less the same blue, with a high level of compression, it becomes all blue and takes just a few bytes to store. The thing is, the iMovie app doesn’t support the use of special characters when exporting files. In compression, algorithms scan regions of an image or both regions of frames and differences between frames in video to find patterns or approximations. Rob then imported his file into iMovie, chose the lowest resolution of 540p, and got an estimate that the output file would be even bigger: 166.8MB! He asks, “Surely, there must be some catch I don’t know about…” This seems counterintuitive, but it comes from how video files are stored, played back, and export. Rob notes he exported his 720p file at 480p, and got a larger file in result. But the more significant issue here is what’s missing entirely: export options.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)